Erasure (along with its cousin “blackout poetry”) is the technique of omitting parts of an existing text (whether poem, article, reprint of a speech, a novel or an excerpt) to create a poem. With blackout poetry, the text is left as is with the omitted words, phrases and sentences marked out. Part of its appeal is its dramatic presentation. Erasure typically reorganizes the remaining text perhaps into stanzas.

Some poets take full poetic license in erasure by changing the wording or the forms of words and even combining letters to create words not found in the original as long as the words/letters remain in the original sequence. I admit I truly enjoyed cutting the text of Mike Huckabee’s speech to have him seemingly admit to a torrid desire for a shirtless Vladimir Putin.

While my erasure of Huckabee’s speech was merely silly, erasure is a great technique to use for political snark and for knifepoint observations. A recent article in Fast Company noted the form’s skill in delivering harsh truth. The poet Isobel O’Hare recently applied erasure to the recent statements from celebrities accused of sexual harassment and posted these blackout poems to Instagram. For more examples, check out her website.

Full disclosure, I first came upon Isobel O’Hare’s poems on the Poetry Foundation's Harriet blog, and the next day my stepson sent me a link to her poetry.

I first tried erasure at Poetry Lab, the inspiring generative workshop run by Danielle Mitchell. This prompt is hers. She gave everyone this block of text from Virginia Wolf’s The Voyage Out and required that we cut it down to just twenty words.

Your prompt is to do the same. Cut this text down to just twenty words:

Chapter XIV

The sun of that same day going down, dusk was saluted as usual at the hotel by an instantaneous sparkle of electric lights. The hours between dinner and bedtime were always difficult enough to kill, and the night after the dance they were further tarnished by the peevishness of dissipation. Certainly, in the opinion of Hirst and Hewet, who lay back in long arm-chairs in the middle of the hall, with their coffee-cups beside them, and their cigarettes in their hands, the evening was unusually dull, the women unusually badly dressed, the men unusually fatuous. Moreover, when the mail had been distributed half an hour ago there were no letters for either of the two young men. As every other person, practically, had received two or three plump letters from England, which they were now engaged in reading, this seemed hard, and prompted Hirst to make the caustic remark that the animals had been fed. Their silence, he said, reminded him of the silence in the lion-house when each beast holds a lump of raw meat in its paws. He went on, stimulated by this comparison, to liken some to hippopotamuses, some to canary birds, some to swine, some to parrots, and some to loathsome reptiles curled round the half-decayed bodies of sheep. The intermittent sounds—now a cough, now a horrible wheezing or throat-clearing, now a little patter of conversation—were just, he declared, what you hear if you stand in the lion-house when the bones are being mauled. But these comparisons did not rouse Hewet, who, after a careless glance round the room, fixed his eyes upon a thicket of native spears which were so ingeniously arranged as to run their points at you whichever way you approached them. He was clearly oblivious of his surroundings; whereupon Hirst, perceiving that Hewet's mind was a complete blank, fixed his attention more closely upon his fellow-creatures. He was too far from them, however, to hear what they were saying, but it pleased him to construct little theories about them from their gestures and appearance.

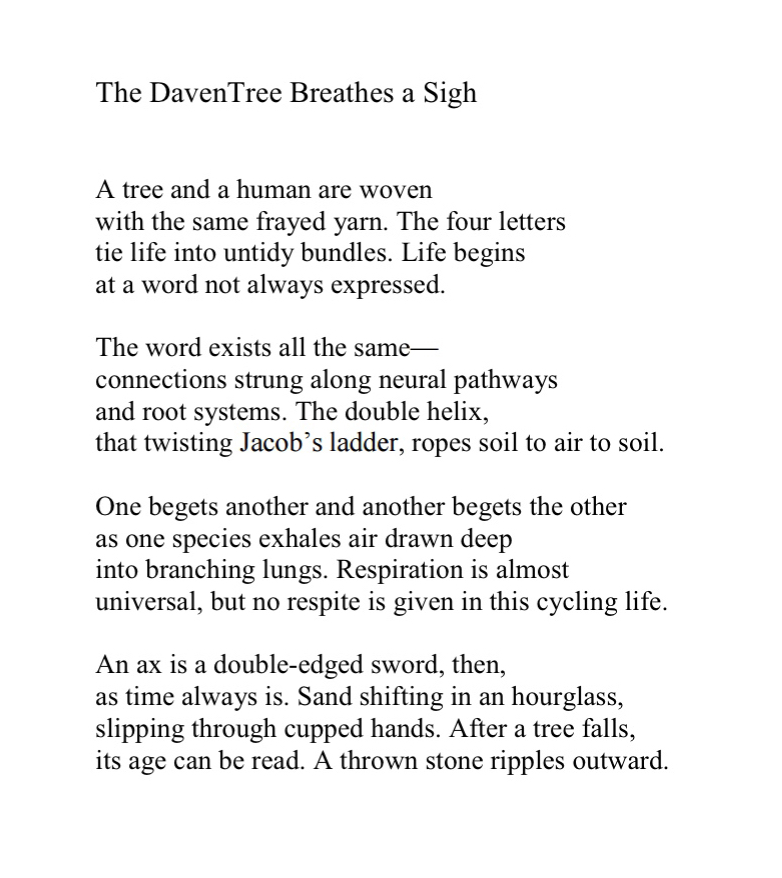

Here is my rough process (scribbled, crumpled and torn):